Baby in the Booth: a Three Letters origin story

In the spring and summer after my son was born, I would carry him in a wrap to the Barnes and Noble on Court Street near my apartment in Brooklyn. I would sit cross-legged on the carpet in the children’s section and read with him propped up on my lap. I read aloud and faced him towards the pages, though he was a newborn, more or less, and so he did not speak or understand words. Nor were his brain or his eyes or the connective stuff between the eyes and brain developed enough to make sense of pictures. What he really liked were simple black and white designs like the ones on the cards we would dangle over his Moses basket in the living room of our apartment. Oh, he looked all around at those black and white cards while we played Miles Davis and Bach and The Beatles, trying to make for ourselves a genius. Now I have two kids so I can laugh at these early days. Ha ha ha ha, what you don’t know about parenthood is everything, Self.

Pleased as I was with myself in the throes of early motherhood, I was not so delusional that I imagined my son absorbing any meaning out of the books we read together at Barnes and Noble. My purpose for the visit was firstly, to get out of the house and go somewhere with a good changing table in the bathroom and secondly, to familiarize myself with the Children’s Book genre. My parents did not read aloud to me as a child. They were social, busy people and it was just not the sort of thing they did. I heard books read aloud on the colorful rug in the school library. I learned to read young so I could absorb them by the stack on my own. But I have no memory of sitting down beside a parent and being read to. I planned to do everything differently than my parents did which started with living in a small apartment in New York City instead of a big house in the Chicago suburbs and carried on through natural birth, breastfeeding, reading to my kids, limiting television, the whole bit.

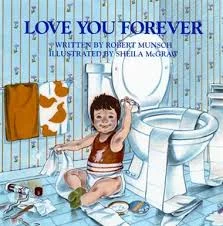

I was excited to see what was in store for my son and I in the world of children’s lit. I looked through the bestsellers that came after my time: the great Mo Willems books, Pete the Cat, Dragons Love Tacos. But I also went back to books I remembered vaguely from the kind librarians of my own childhood: Eloise (really long, with a lot of smoking), Curious George (a monkey menace who never listens), Make Way for Ducklings (deadbeat dad abandons wife with eight kids and no transportation), others. My best friend’s mother was a retired first grade teacher, and she gave me a number of titles she read to her own children and to her students for years. Her favorite above all is one of the bestselling picture books of all time called Love you Forever. I’d never heard of it. I found it, read it aloud to my infant, he passed out on me and so I did all the crying. That book is a dick.

I’m not a masochist and so I did not purchase the book. It was 2013, Obama was president, I had a new baby and hope in my heart. Sweetly, in charming painted pictures, the book tells the story of a loving mother who cares for her son with borderline-creepy intensity until she gets old and frail and he then cares for her in the same way, rocking the nearly dead supermom in his arms and I’ll stop there because, like I said, that book is a dick.

I could not believe that thing was my best friend’s mother’s favorite book. I went home that night and told my husband Gregory about it. I described the story in the book. My husband erupted in breathless sobs—from my description. Never, not in the ten years we were together before my son’s birth, had I seen more than a damp cheek at the end of an exceptionally tragic movie. But this was real grief and anger and fear. He could not stop it or control it. He could only expel it.

I tell this story because I think it illustrates an under-reported side effect of having children, which is the sudden accessibility of our own childhoods, especially the traumatic parts. Gregory lost his own mother when he was a teenager. The birth of our son re-introduced a mortal mother to his life, namely me. That I could die, leaving our son motherless, cut to the very core of my husband’s soul, and that stupid book articulated that too perfectly. Whatever protections he’d built up since his mother’s death to make it through his daily life were torched the second he held our kid in his arms.

Hell, it was happening to me, too. I was really into my baby—attentive to a degree that I can say for certain nobody attended to me. And probably that sounds whiny and like I’m complaining about what was a truly privileged upbringing, but you can have a lot of stuff without having what you need. Also, it was my pleasure to love and care for my tiny child who never asked to be born. But as I slept with, fed, changed, carried, attended to my baby, that shit came up. It does. It comes up and maybe you feel grateful for what your parents did for you. Or maybe, like me, you wonder what they were so busy doing instead.

It’s a vulnerable place; one that I thought could be a fruitful moment to explore in fiction. And so, I imagined a story in which a new mother, who’d spent her adulthood like the rest of us, building up ways to shield herself from her past, finds that the birth of her child has rendered those shields useless. In Three Letters, the protagonist, Ariel Frank, has allowed herself to become comfortable in her estrangement from her sister. But with the birth of her first baby, she finds herself haunted by the sister’s absence:

The only threat to her even balance came from memories, more vivid and powerful than before, that lay in wait for her in unexpected places, catching her off-guard. A song that came to mind while trying to get Callie down for a nap, the smell of baby soap, the ruffles around the cuff of a baby sock, anything and everything could suck her back into her own childhood. Images of her mother and most frustrating of all, her sister, ambushed her a million times a day. Erica, her fellow child, roommate, co-participant in Ariel’s upbringing had been her partner in life for years. But where was she now?

When I was pregnant the first time, it annoyed me when people would say things like, “Your life is going to totally change in ways you can’t possibly understand now!” Great, I would think, but so if I can’t possibly comprehend this change that is coming for me, why even discuss it? Maybe just tell me I’m glowing and pass the popcorn, be helpful. Now that I’m on the other side, I think what most people mean by that is the shift in focus that naturally happens when a person comes into your life whose survival matters more to you than your own. It’s like you’d spent your whole life on stage, in the spotlight, the marquee star of your story and then your kid is born and suddenly you’re way back in the booth, working the lights. And that does not always feel so good. Especially if you’re a mother you might wonder where the applause went and also the beautiful costumes and also the enormous space you used to take up in the world.

But this other thing that happens is that the child that you were a long time ago comes out from the shadows. Maybe she’s in the booth with you, laying a little hand on yours as you work the dimmer, watching the show along with you. And you love that kid, too. Just a kid, like your own kid. Sweet little thing. Having that innocent child that you were suddenly right next to you is a beautiful and a hard thing to live with while you try to keep your babies alive.